Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization

2021 Language Assistance Plan

Project Manager

Betsy Harvey

Project Principal

Jonathan Church

Data Analyst

Margaret Atkinson

Graphics

Ken Dumas

Cover Design

Kim DeLauri

The preparation of this document was supported

by Federal Highway Administration through

MPO Combined PL and 5303 #112310.

Central Transportation Planning Staff is

directed by the Boston Region Metropolitan

Planning Organization (MPO). The MPO is composed of

state and regional agencies and authorities, and

local governments.

For general inquiries, contact

Central Transportation Planning Staff 857.702.3700

State Transportation Building ctps@ctps.org

Ten Park Plaza, Suite 2150 ctps.org

Boston, Massachusetts 02116

The Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) operates its programs, services, and activities in compliance with federal nondiscrimination laws including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987, and related statutes and regulations. Title VI prohibits discrimination in federally assisted programs and requires that no person in the United States of America shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national origin (including limited English proficiency), be excluded from participation in, denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to discrimination under any program or activity that receives federal assistance. Related federal nondiscrimination laws administered by the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, or both, prohibit discrimination on the basis of age, sex, and disability. The Boston Region MPO considers these protected populations in its Title VI Programs, consistent with federal interpretation and administration. In addition, the Boston Region MPO provides meaningful access to its programs, services, and activities to individuals with limited English proficiency, in compliance with U.S. Department of Transportation policy and guidance on federal Executive Order 13166.

The Boston Region MPO also complies with the Massachusetts Public Accommodation Law, M.G.L. c 272 sections 92a, 98, 98a, which prohibits making any distinction, discrimination, or restriction in admission to, or treatment in a place of public accommodation based on race, color, religious creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, disability, or ancestry. Likewise, the Boston Region MPO complies with the Governor's Executive Order 526, section 4, which requires that all programs, activities, and services provided, performed, licensed, chartered, funded, regulated, or contracted for by the state shall be conducted without unlawful discrimination based on race, color, age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, religion, creed, ancestry, national origin, disability, veteran's status (including Vietnam-era veterans), or background.

A complaint form and additional information can be obtained by contacting the MPO or at http://www.bostonmpo.org/mpo_non_discrimination.

To request this information in a different language or in an accessible format, please contact

Title VI Specialist

Boston Region MPO

10 Park Plaza, Suite 2150

Boston, MA 02116

civilrights@ctps.org

By Telephone:

857.702.3702 (voice)

For people with hearing or speaking difficulties, connect through the state MassRelay service:

For more information, including numbers for Spanish speakers, visit https://www.mass.gov/massrelay

Abstract

Executive Order 13166—Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency (LEP)—directs recipients of federal funding to “ensure that the programs and activities they normally provide in English are accessible to LEP persons and thus do not discriminate on the basis of national origin in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” In response to subsequent rules and regulations developed by the United States Department of Transportation, this Language Assistance Plan (LAP) describes the language needs of residents within the 97 municipalities served by the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) and the oral and written language assistance that the MPO provides to meet those needs. As the MPO is a recipient of federal funding from the Federal Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration, this LAP meets the requirements set forth by these agencies regarding the provision of language assistance in the MPO’s activities and programs.

ES.2.. Determining Language Needs.

ES.2.1 Number and Proportion of People with LEP in the Boston Region

ES.2.3 Nature and Importance of the MPO’s Programs, Services, and Activities

ES.2.4 Resources Available to the MPO

ES.3.. Providing Language Assistance

ES.3.1 Oral Language Assistance

ES.3.2 Written Language Assistance

ES.4.. Monitoring and Updating the Plan

1.2...... Federal Regulatory Background

Chapter 2—Determining Language Needs

2.1...... Factor 1: Number and Proportion of People with LEP in the Boston Region

2.1.1 Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS)

2.1.2 Massachusetts Department of Education Data

2.2...... Factor 2: Frequency of Contact

2.3...... Factor 3: Nature and Importance of the MPO’s Programs, Services, and Activities

2.4...... Factor 4: Resources Available to the MPO

Chapter 3—Providing Language Assistance

3.1...... Oral Language Assistance

3.1.1 In-Person Public Engagement

3.1.2 Virtual Public Engagement

3.2...... Written Language Assistance

3.2.3 Emails, Surveys, and Social Media

Chapter 4—Monitoring and Updating the Plan

Table 1 Safe Harbor Languages Spoken in the Boston Region

Table 2 Top Ten Non-English Languages Spoken by English Language Learners

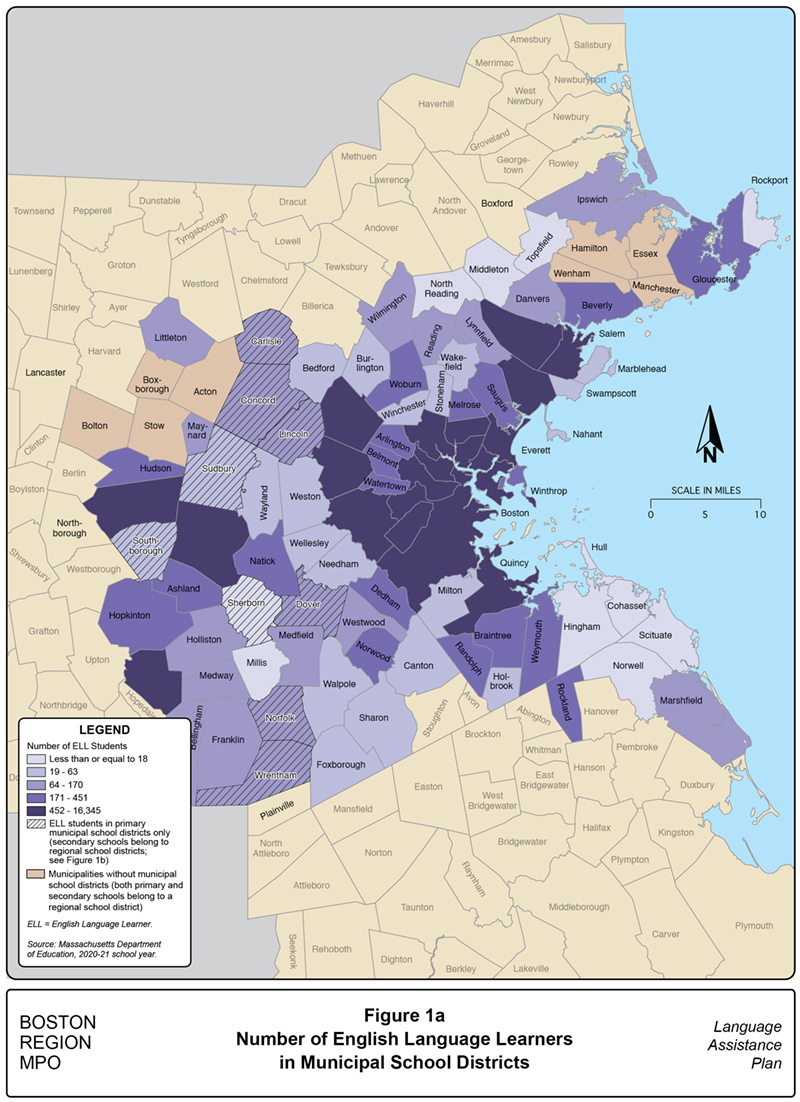

Figure 1a Number of English Language Learners in Municipal School Districts

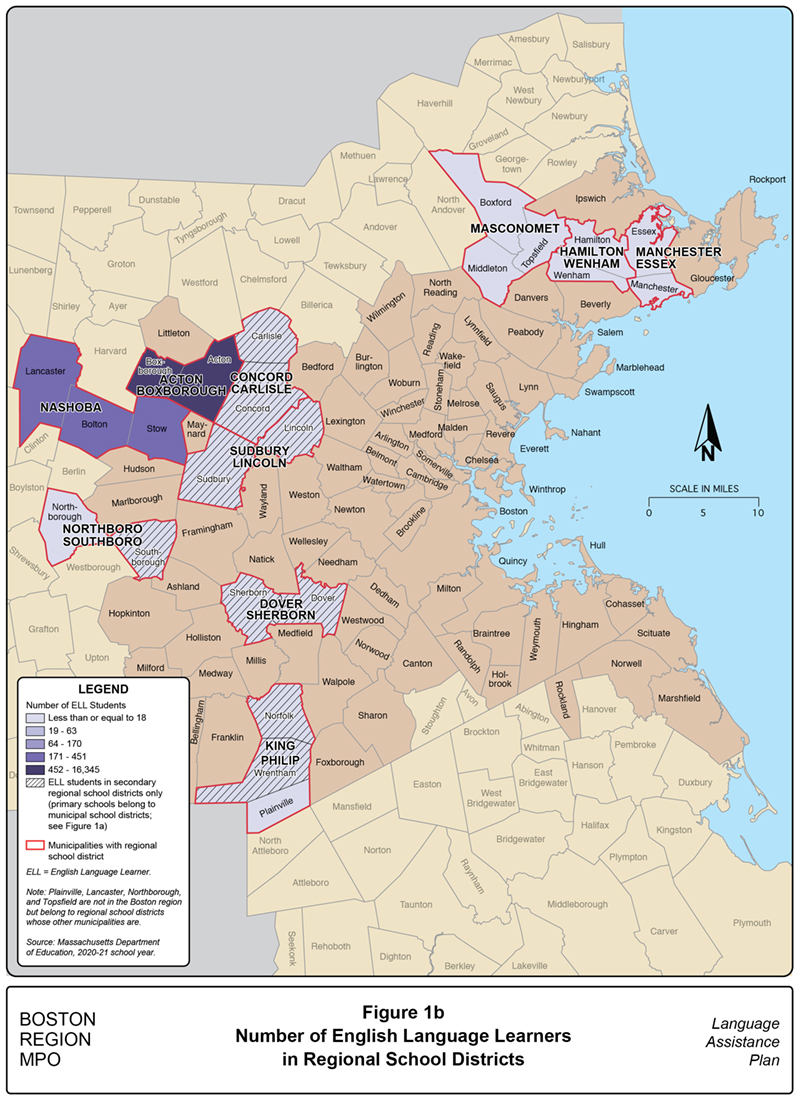

Figure 1b Number of English Language Learners in Regional School Districts

As a recipient of federal funding from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is required to comply with federal civil rights statutes and executive orders. These laws include Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin. Executive Order 13166—Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency (LEP)—clarifies that national origin protections include people with LEP. It instructs recipients of federal funding to provide meaningful language access to their services. As instructed by United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) regulations, this Language Assistance Plan (LAP) describes the population with LEP living in the 97 municipalities in the Boston region and the MPO’s approach to providing meaningful language assistance.

Chapter 2 of the LAP describes the results of the “four-factor” analysis required by recipients of federal funding by USDOT. The analysis describes the population with LEP in the Boston region, the MPO’s programs and services, the frequency with which LEP individuals come in contact with the MPO’s programs and services, and the MPO’s resources to provide language assistance.

In the past, MPO staff relied on the American Community Survey (ACS) summary tables, as those provided the most detailed information on the number of people with LEP in the Boston region and the languages they speak. Since the MPO’s last LAP was published in 2017, the ACS changed how languages are categorized in the summary tables and updated the controls placed on the data to protect respondents’ privacy. As a result, the ACS summary tables no longer provide sufficient language detail to satisfy the federal requirements for LAPs.

To meet those requirements, staff turned to the US Census Bureau’s Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) data. While PUMS data uses the same raw data that underpins the ACS summary tables, it contains individual person or household records, allowing users to create detailed data tables that would not be possible to create with the pre-tabulated ACS summary tables. However, to protect privacy PUMS data are aggregated to larger geographies called Public Use Microsample Areas (PUMA), which do not align perfectly with the Boston region’s boundary. By estimating the share of people in the portion of PUMAs within the Boston region, staff were able to determine the number and share of people who speak non-English languages and who have LEP to a level of detail not available with ACS summary tables.

MPO staff collected 2015–19 PUMS data, which show that 11.2 percent of people in the Boston region have LEP. Twenty-six languages meet the “Safe Harbor” threshold of having at least 1,000 speakers or five percent of the total LEP population, whichever is less. Spanish (36.5 percent), Chinese (16.7 percent), Portuguese (11.3 percent), Haitian (7.1 percent), and Vietnamese (5.0 percent) continue to be the five most widely spoken languages by people with LEP in the Boston region.1

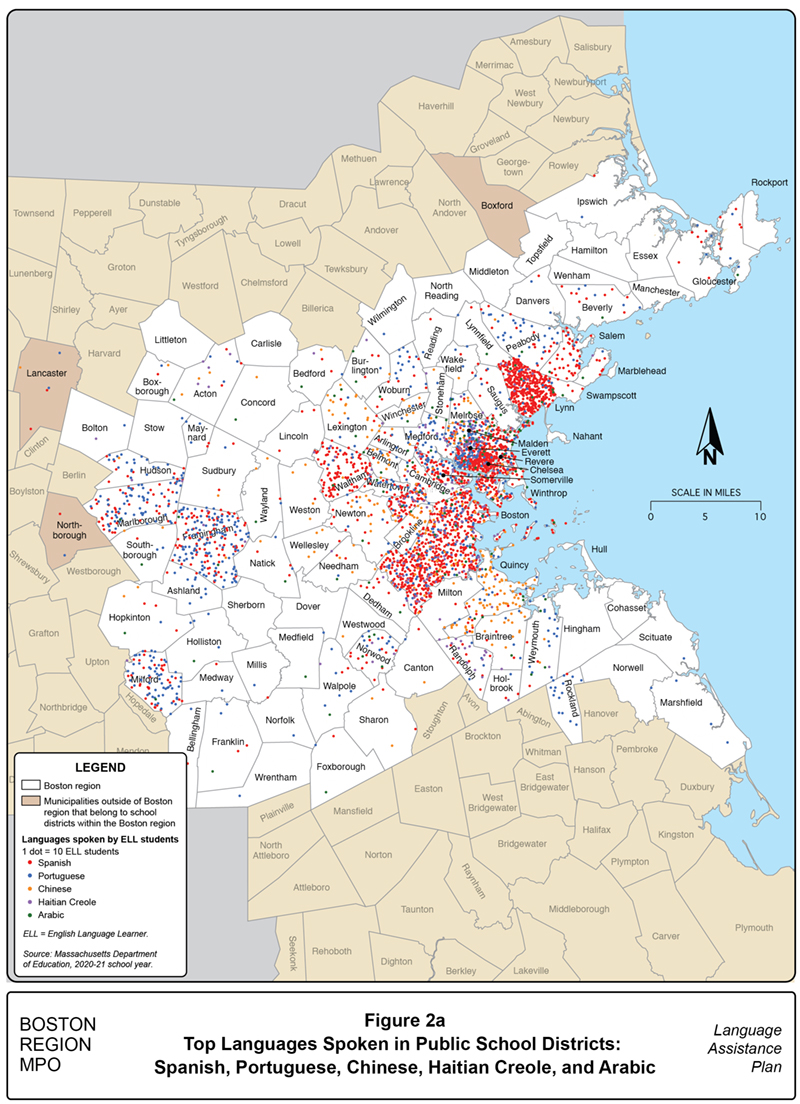

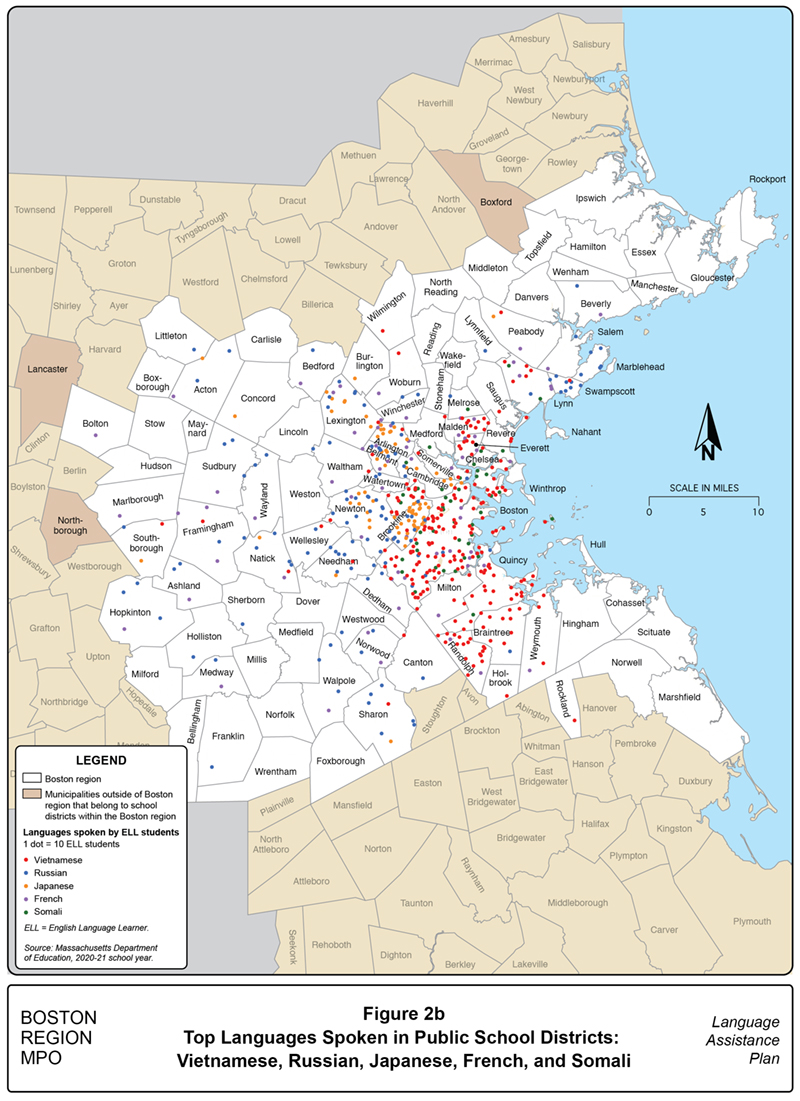

To get more detail on where within the Boston region these languages are spoken, staff analyzed language data for public municipal and regional school districts. The Massachusetts Department of Education (MDOE) collects data on the number of English language learners (ELLs) and the languages they speak. Spanish (52.6 percent), Portuguese (18.3 percent), Chinese (5.9 percent), Haitian Creole (5.0 percent), and Arabic (2.9 percent) are the five most widely spoken languages by ELLs. This more detailed data also allows MPO staff to see in which municipalities each language is spoken, which assists in public outreach.

The MPO has infrequent contact with people with LEP. Contact most often occurs through the MPO’s online communications, such as the website, emails, and surveys. MPO staff also conduct outreach activities in communities where people with LEP reside and with organizations that involve people with LEP. These activities most often support the development of the MPO’s certification documents—the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), and Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). However, other events also occur throughout the regular course of the MPO’s public engagement activities.

The MPO conducts transportation studies, chooses transportation projects to fund, conducts long-range planning, and provides technical assistance. While the denial or delay of access to these activities would not have immediate or life-threatening implications for people with LEP, transportation improvements resulting from the MPO’s decisions have an impact on all residents’ mobility and quality of life. Public engagement is critical to the success of the MPO’s activities and programs. As such, MPO staff make every effort to ensure that all people, regardless of the language they speak, have the opportunity to provide input on how regional transportation planning is carried out.

Based on the number and type of meetings for which written materials must be translated, the MPO has budgeted sufficient funds to translate vital documents into the five languages most widely spoken by people with LEP in the region, as identified through this LAP. The budget also includes sufficient funds to translate documents into other languages, as needed, for public outreach or to accommodate requests. In addition, the MPO has sufficient resources to provide interpreter services as requested or needed at MPO-sponsored meetings and outreach events.

The MPO provides language assistance at both in-person and online public engagement events. At MPO board meetings, interpreter services may be requested at least seven days in advance for both in-person meetings and virtual meetings. Staff also conduct public outreach events specifically in communities where people with LEP reside and with organizations that involve people with LEP. To determine language assistance needs, staff rely on data collected for this LAP and coordinate with local partners. Because ACS and MDOE data are not always detailed enough, local partners are critical to enabling the MPO to provide appropriate interpreter services that are tailored to the community.

The MPO provides written translations of “vital documents,” as required by federal regulations. Vital documents are those that contain information that is critical for obtaining MPO services or that are required by law. The following documents and materials are considered vital documents:

These documents are translated into, at minimum, the five languages most widely spoken by people with LEP in the region: Spanish, Chinese (simplified and traditional), Portuguese, Haitian, and Vietnamese. Any member of the public may request a translation of any MPO document into a language not regularly provided.

To accommodate website translation needs, the MPO website hosts Google Translate, a browser-based tool that translates website content into more than one hundred languages, including all Safe Harbor languages within the Boston region. All content on the MPO’s website is available in HTML format so that Google Translate can provide a translation. Additionally, using Google Translate, all emails from the MPO can be translated into dozens of languages. Surveys, which staff frequently use and which are primarily distributed online, are translated into Spanish, Chinese (simplified and traditional), Portuguese, Haitian, and Vietnamese.

MPO staff continue to monitor the changing language needs of the region and

to update language assistance services as appropriate. Staff continuously explore new sources of data that provide a more nuanced understanding of the language needs of residents in the region. MPO staff will continue to strive to improve its engagement of people with LEP and community organizations that serve them. As new language data become available and approaches to assisting people with LEP evolve, this LAP will be revised.

The policy of the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is to ensure that people with limited English proficiency (LEP) are neither discriminated against nor denied meaningful access to and participation in the programs, activities, and services provided by the MPO. This Language Assistance Plan (LAP) describes how MPO staff provide appropriate language assistance to people with LEP by assessing language needs, implementing language services that provide meaningful access to the MPO’s transportation planning process, and publishing information regarding these services without placing undue burdens on the MPO’s resources.

Conducting meaningful public engagement is a core function of the MPO, critical to ensuring that regional transportation planning is conducted in a fair and transparent manner. While this LAP is designed to meet federal requirements, it also supports the MPO staff in the development and implementation of public engagement and communication efforts. These efforts are described in the MPO’s Public Outreach Plan (POP). This update to the LAP was developed in coordination with the most recent POP.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination by federal agencies

and recipients of their financial assistance on the basis of national origin, which is signified by LEP. Further, Executive Order 13166, Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency, was signed on August 11, 2000, directing federal agencies and recipients of federal financial assistance (such as MPOs) to provide meaningful language access for people with LEP to agency services. In response to these regulations, the United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) published policy guidance in 2005 for its recipients of financial assistance, describing recipients’ responsibilities to provide meaningful access for people with LEP and identifying the factors they must consider when doing so.

To fulfill these responsibilities, the Boston Region MPO has developed a LAP based on guidance from the USDOT and Federal Transit Administration (FTA). This LAP is updated every three years. As specified in FTA Circular 4702.1B, the LAP assesses the following four factors when determining language needs of people with LEP served by the MPO:

Chapter 2 describes the results of this four-factor analysis.

Chapter 2—Determining Language Needs

The following sections discuss each of the four factors listed in the previous chapter and describes the results of the analysis completed for each factor.

In previous LAPs, MPO staff used American Community Survey (ACS) summary tables to identify the languages spoken by people with LEP living within the Boston region. However, starting with the 2016 ACS, the US Census Bureau changed how it reports non-English languages spoken at home in ACS summary tables. Coding for languages spoken at home was updated to reflect the changes in the number of people who speak different languages, resulting in the addition of some new languages and the reorganization of others (for example, French Creole became Haitian). In addition, in an effort to protect the privacy of the speakers of less widely spoken languages, at smaller geographies these languages have been collapsed and reported in aggregated form with others in the same language family (such as Other Indo-European Languages).2

In the past, data were collected by municipality and aggregated to the MPO region to determine the number and percent of people with LEP; however, many languages are no longer reported for smaller municipalities. This means that MPO staff could not identify many of the individually spoken languages that were identified in the last (2017) LAP using ACS summary tables. To overcome these challenges, staff gathered language data from other sources to provide a fuller picture of language needs in the Boston region.

The Census Bureau’s PUMS data use the same raw data gathered for the ACS but are provided as untabulated records of individual people or housing units to allow users to create custom tables that are not available in the summary tables created for standard ACS products. Because of the disaggregated nature of the data, they are subject to more stringent privacy controls. These controls limit the size of the geographic areas for which data can be identified. The smallest area for which PUMS data are available is the Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA).

PUMAs are PUMS-specific geographies that have a population of 100,000 to approximately 200,000 people. They are based on continuous aggregations of tracts or counties within a state. While some PUMAs within the Boston region align with the MPO’s boundaries, a few do not.3 However, PUMS data do provide the level of detail regarding languages spoken at home by people with LEP as required by FTA regulations; PUMS data are, therefore, the best option for the MPO to comply with federal requirements.

Although the population with LEP in the Boston region can be identified using standard ACS summary tables, in order to be consistent with how non-English languages spoken are identified, this LAP uses ACS PUMS data to report both types of information. According to data from the 2015–19 PUMS, 11.2 percent (349,345 people) of the region’s population of 3,114,612 who are five years of age and older have LEP. The largest proportion of people with LEP speak Spanish (36.5 percent), followed by Chinese (either Mandarin or Cantonese) (16.7 percent), and Portuguese or Portuguese Creole (11.3 percent). Altogether, these three languages represent almost two-thirds (64.6 percent) of people in the region with LEP.

USDOT guidance specifies circumstances that signify strong evidence of a recipient’s compliance with their written translation obligations. If a recipient provides written translation of vital documents into languages that meet a certain threshold—called “Safe Harbor languages”—then their obligation is likely met. Safe Harbor languages are those non-English languages that are spoken by people with LEP (of those eligible to be served or likely to be affected or encountered by the recipient) who make up at least five percent of the population or 1,000 individuals, whichever is less. In the Boston region, Safe Harbor languages include speakers of the languages in Table 1. There are 33 Safe Harbor languages in the Boston region.4 Because the cost of providing translations in all 33 Safe Harbor languages is prohibitive, and as the top five languages make up over three-quarters of all languages spoken by people with LEP in the region, the MPO focuses its written translation resources on those five languages: Spanish, Chinese (traditional and simplified), Portuguese, Haitian, and Vietnamese.5 (See Chapter 4 for details.)

The comparison between this LAP and the one completed in 2017 is imperfect. A full comparison of data from the MPO’s last LAP is not possible due to the changes in how ACS language data are categorized and the privacy controls, as described above. Some individual languages can be compared, however. Where possible, Table 1 shows the percent change in the number of people with LEP for each language since the last LAP was completed in 2017. For that LAP, data were used from the 2010–14 ACS summary tables. Because the years for the data used in this and the 2017 LAP are not overlapping, they can be compared for those languages that the Census Bureau recommends.6 The geographies used to aggregate the data differ, however, as does the coding of some languages. Therefore, readers should compare data with caution and focus on the directionality and magnitude of the percent change between the LAPs, rather than the precise number.

Table 1

Safe Harbor Languages Spoken in the Boston Region

| Language |

Number of Speakers1 |

Percent Change from the 2017 LAP |

Percent of People with LEP |

Percent of Boston Region Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Spanish |

126,018 |

19.6% |

36.5% |

4.0% |

Chinese (including Mandarin and Cantonese) |

57,687 |

15.6% |

16.7% |

1.9% |

Portuguese and Portuguese Creoles |

39,144 |

12.5% |

11.3% |

1.3% |

Haitian2 |

24,623 |

14.2% |

7.1% |

0.8% |

Vietnamese |

17,361 |

15.1% |

5.0% |

0.6% |

Russian |

11,236 |

-4.5% |

3.3% |

0.4% |

Arabic |

7,124 |

-26.9% |

2.1% |

0.2% |

Italian |

5,871 |

-24.7% |

1.7% |

0.2% |

French (including Cajun)3 |

5,574 |

3.8% |

1.6% |

0.2% |

Other Indo-European languages |

5,447 |

N/A |

1.6% |

0.2% |

Korean |

4,474 |

16.1% |

1.3% |

0.1% |

Greek |

3,909 |

5.6% |

1.1% |

0.1% |

Amharic, Somali, or other Afro-Asiatic languages |

3,652 |

N/A |

1.1% |

0.1% |

Japanese |

2,903 |

5.6% |

0.8% |

0.1% |

Nepali, Marathi, or other Indic languages |

2,810 |

N/A |

0.8% |

0.1% |

Khmer |

2,629 |

16.4% |

0.8% |

0.1% |

Hindi |

2,500 |

21.2% |

0.7% |

0.1% |

Other languages of Asia |

2,323 |

N/A |

0.7% |

0.1% |

Yoruba, Twi, Igbo, or other languages of Western Africa |

1,794 |

N/A |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Gujarati |

1,745 |

11.7% |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Swahili or other languages of Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa |

1,658 |

N/A |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Polish |

1,639 |

-6.2% |

0.5% |

0.1% |

Tagalog (including Filipino) |

1,319 |

-4.2% |

0.4% |

0.0% |

Serbo-Croatian |

1,308 |

N/A |

0.4% |

0.0% |

Persian (including Farsi and Dari) |

1,304 |

4.6% |

0.4% |

0.0% |

Ukrainian or other Slavic languages |

1,261 |

N/A |

0.4% |

0.0% |

Thai, Lao, or other Tai-Kadai languages |

1,228 |

N/A |

0.4% |

0.0% |

Other and unspecified languages |

1,171 |

N/A |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Bengali |

1,147 |

N/A |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Telugu |

1,134 |

N/A |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Armenian |

1,124 |

30.9% |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Punjabi |

1,094 |

N/A |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Tamil |

1,007 |

N/A |

0.3% |

0.0% |

Total LEP Safe Harbor Language Speakers |

345,218 |

20.5% |

98.8% |

11.2% |

Total LEP Population |

349,345 |

12.3% |

100.0% |

11.2% |

Total Population Age 5 or Older |

3,114,612 |

4.3% |

N/A |

100.0% |

1 Of the population that is five years of age or older, people with LEP include those who self-identify as speaking English well, not well, or not at all.

2 Prior to 2016, French-based creole languages were coded as French Creole. Because most of these speakers speak Haitian Creole, starting in 2016 Haitian Creole was recoded to Haitian, which includes Haitian Creole and all other mutually intelligible French-based creoles.

3 Prior to 2016, Patois was grouped with French. Starting in 2016, Patois was usually coded as Jamaican Creole English, unless a more appropriate code was available.

LAP = Language Assistance Plan. LEP = Limited English proficiency. MPO = Metropolitan Planning Organization. N/A = Not available.

Source: American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, 2015–19; and 2010–14 American Community Survey summary tables.

The data show that there has been an increase in the number of people with LEP regionwide. This increase is concentrated among people who speak certain languages. More people with LEP speak one of the MPO’s Safe Harbor languages; there are now 33 Safe Harbor languages, which is an increase from the 19 documented in the 2017 LAP. Additionally, there has been an increase in the percent of people with LEP who speak Safe Harbor languages. Spanish, the most widely spoken non-English language in the region, saw a large increase. Of all languages, Armenian saw the largest percent increase. There was a consistent increase in the share of speakers of languages in Asia—including Khmer, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, and Persian. Additionally, several languages are new to the Safe Harbor languages, including Punjabi, Tamil, and Bengali. However, five languages saw a decline in the number of speakers: Arabic, Italian, Polish, Russian, and Tagalog.

In light of the changes to how ACS summary table language data are reported and the course geography used for PUMS data, MPO staff sought out other sources of data about languages spoken by people with LEP that are available at a smaller geography. Some Massachusetts state agencies provide language data about the people that they serve, including the Massachusetts Department of Education (MDOE). MPO staff looked at public school districts (municipal and regional school districts) within the Boston region. The MDOE collects data on the number of students who are English language learners (ELL) in each school district, as well as the languages they speak.7 It can be assumed that if a student is an ELL, their parents are likely not proficient in the English language. While these data do not correlate perfectly with the USDOT’s LEP definition, they allow staff to identify where language needs are presents at smaller geographies, which is especially helpful when staff conduct public outreach in communities in the Boston region. According to 2020–21 school year data, 11.8 percent of primary and secondary school students in public districts in the Boston region were ELLs, out of 413,881 students. That figure is very close to the 11.1 percent of people with LEP in the region as reported in the PUMS data.

Figure 1a shows the number of ELL students in municipal public school districts, while Figure 1b shows the number of ELL students in regional public school districts in the Boston region.8 The school districts with the most ELL students are those in and around Boston, as well as those in and around Framingham.

#

#

The table below shows the ten non-English languages spoken most frequently by ELLs.

Table 2

Top Ten Non-English Languages Spoken by English Language Learners

Language |

Number of ELL Students |

Percent of Students |

Spanish |

24,608 |

52.6% |

Portuguese (including Cape Verdean Creole) |

8,579 |

18.3% |

Chinese |

2,762 |

5.9% |

Haitian Creole |

2,350 |

5.0% |

Arabic |

1,372 |

2.9% |

Vietnamese |

1,156 |

2.5% |

Russian |

662 |

1.4% |

Japanese |

401 |

0.9% |

French |

399 |

0.9% |

Somali |

282 |

0.6% |

ELL = English language learner.

Source: Massachusetts Department of Education, 2020–21 school year.

Figures 2a and 2b, below, show the distribution of these top ten languages, in municipal and regional school districts. Note that the dots are randomly distributed within each school district and do not represent the actual locations of ELL students.

#

#

In terms of the languages that are most commonly spoken, the magnitude of the MDOE data align with PUMS data. Spanish is the most widely spoken language among ELLs, followed by Portuguese, Chinese, and Haitian Creole. However, the percent of ELLs does not always match the ACS data. For three languages, there is a higher percentage of ELL speakers than people with LEP. While 36.5 percent of people with LEP speak Spanish, over half of all ELLs do. Portuguese speakers make up 11.3 percent of people with LEP but 18.3 percent of ELLs. Arabic speakers make up 2.1 percent of people with LEP but 2.9 percent of ELLs. Several languages have a lower share of ELLs than people with LEP: Chinese (5.9 percent compared to 16.7 percent), Haitian (5.0 percent compared to 7.1 percent), Vietnamese (2.5 percent compared to 5.0 percent), Russian (1.4 percent compared to 3.3 percent), French (0.9 percent compared to 3.8 percent), and Somali (0.6 percent compared to 1.1 percent).9 Japanese is about the same among both groups (0.8 percent compared to 0.9 percent).

These data suggest that for those who speak Chinese, Haitian, French, Vietnamese, and Russian, it is more often older adults or adults without children who have a greater need for language services, whereas for Portuguese and Spanish, it is more likely that children and their families require services. This is important information that can help the MPO tailor outreach more effectively based on the communities and languages that are spoken.

The MPO has infrequent and unpredictable contact with people with LEP, largely because of the nature of MPO programs and activities. Online avenues for contact are the MPO website, TRANSREPORT blog, MPO emails, and online surveys. Other occasions for contact with people with LEP include when staff participate in meetings held by organizations that include people with LEP and MPO-hosted events, such as public workshops and open houses. Some meetings are held in concert with the development of the MPO’s certification documents—the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), and Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP)—while others are done during the course of regular public engagement activities conducted throughout the year.

The MPO plans and funds transportation projects and carries out studies within the Boston region. While the MPO does not provide transportation services or implement improvements directly, and although denial or delay of access to the MPO’s programs and activities would not have immediate or life-threatening implications for people with LEP, transportation improvements resulting from the MPO’s decisions have an impact on all residents’ mobility and quality of life.

Projects selected to receive federal funding by the MPO progress through planning, design, and construction stages under the responsibility of municipalities, state transportation agencies, and regional transit authorities. These implementing agencies have their own policies in place to provide opportunities for people with LEP to shape where, how, and when a project is implemented. MPO staff focus their language assistance efforts on the work tasks on which MPO dollars are spent.

Input from all stakeholders is critical to the transportation planning process, so the MPO invests considerable effort to conduct inclusive public engagement. Staff helps the public to understand the transportation planning process and provides ongoing opportunities for the public to shape transportation in the Boston region. The specific public engagement activities carried out by staff are described in the MPO’s POP.

Staff conduct public engagement to support carrying out the MPO’s core functions. Core functions include the development of the MPO’s three certification documents, MPO-funded studies, projects, and civil rights and environmental justice-related activities. These functions provide structured opportunities for staff to ensure people with LEP can provide meaningful input as this work is carried out. Critically, relationship-building with LEP communities and organizations that represent them is ongoing, whether or not it is for a specific work effort. This work allows staff to build trust, understand needs and effective methods of communication, increase transparency, expand the MPO’s reach, and ensure people with LEP have opportunities to be involved early and often.

Based on the number and type of meetings for which written materials must be translated, the MPO has budgeted sufficient funds to translate vital documents into the five languages most widely spoken by people with LEP, as identified above. The budget also includes sufficient funds to translate documents into other languages, as needed, for public outreach or to accommodate requests. To date, only a few individuals have made such requests.

The MPO’s policy is to provide translation and interpreter services when they are requested at MPO-sponsored meetings. Although the MPO has advertised the availability of interpreters, none have been requested to date. While the MPO has been able to provide language translation services with existing resources thus far, the region is dynamic and continues to attract diverse ethnic and cultural populations. Therefore, the MPO will continue to monitor the need for translation and interpretation services based on factors one through three of the four-factor Analysis and the number of requests received. The MPO will also determine whether the current policy should be adjusted because of resource constraints.

Chapter 3—Providing Language Assistance

The MPO provides interpreter services upon request with two weeks advance notice. Notices for all meetings state this information and how to request an interpreter. The number of people with LEP in the Boston region, along with their infrequent interaction with the MPO, has meant that the MPO is rarely asked to provide oral language services. This, however, does not necessarily mean that there is no need for translation among the region’s population or that this need will not be made known in the future.

Staff also provide interpreters at outreach events where it is expected that people with LEP will attend. Staff study language data from the ACS and schools and talk with local partners to determine potential language needs, as ACS and school data may not be sufficiently localized to get the full picture of language needs. When engaging with the public, staff specifically seek to partner with organizations whose members have LEP and use interpreters to ensure that they can provide input.

The need to conduct public engagement virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic has led staff to expand opportunities to engage with the MPO online. All MPO meetings and MPO-hosted events are held via the Zoom online meeting platform. Staff make every effort to provide services equivalent to those offered at in-person meetings. Attendees may request an interpreter at least two weeks ahead of time.

The MPO provides written translations of vital documents, as required by federal regulations. Vital documents are those that contain information that is critical for obtaining MPO services, or that are required by law. The MPO has determined that documents and materials are considered vital if they enable the public to understand and participate in the regional transportation planning process. These documents include the following:

Staff translates vital documents into, at minimum, the five languages most widely spoken by people with LEP: Spanish, Chinese (simplified and traditional), Portuguese, Haitian, and Vietnamese. The MPO does not translate vital documents into all of the Safe Harbor languages for several reasons: 1) staff do not come into contact with people with LEP on a frequent or regular basis; 2) translation is a resource-intensive effort; and 3) within the MPO region, the top five Safe Harbor languages make up over three-quarters of the non-English languages spoken. Further, the Notice of Nondiscrimination Rights and Protections was developed for use by all Massachusetts MPOs by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT). MassDOT also provided translations of the notice in seven languages: Spanish, Chinese (traditional and simplified), Portuguese, Haitian, Russian, and Vietnamese. The MPO’s complaint form and procedures are translated into eleven languages in addition to English.

The MPO’s approach may not meet all language needs. Based on analyses of MDOE language data, whereas many LEP speakers of the five most common Safe Harbor languages are concentrated in urban areas, especially in and around Boston and Framingham, speakers of the other languages tend to be more geographically dispersed. With that in mind, the MPO’s policy is to identify language needs for areas in which it conducts outreach—for example, public meetings for the LRTP, TIP, or UPWP—and provide written translations in other languages as necessary. To aid in this approach, staff identify the languages spoken in locations where they hold public events through collaboration with community partners.

To accommodate website translation needs, the MPO website hosts Google Translate, a browser-based tool that translates website content into more than one hundred languages, including all Safe Harbor languages within the Boston region. MPO documents are posted on the website as PDF files and in HTML format, which allows them to be read aloud by a screen reader and enables the use of Google Translate for all documents on the website. In addition, people with LEP may also set their internet browser language to one of their choosing.

Email is the main method by which MPO staff communicate with the public. Any member of the public may sign up for any of several MPO email lists. All of these emails can be translated by clicking the appropriate language at the top of the email. Translations are performed by Google Translate and are available in dozens of languages, including all Safe Harbor languages.

MPO surveys are nearly always conducted online because of the frequency with which staff produce surveys, their affordability, and their wide reach. Surveys also allow staff to easily provide multiple translations at a reasonable cost to the MPO. For respondents who access surveys through an MPO email, staff provide links to the translated surveys. Surveys are translated into Spanish, Chinese (simplified and traditional), Portuguese, Haitian, and Vietnamese.

Chapter 4—Monitoring and Updating the Plan

MPO staff continue to monitor the changing language needs of the region and

to update language-assistance services as appropriate. Staff continuously explore new sources of data that provide more nuanced understanding of the language needs of residents in the region and new technologies that expand the reach of MPO activities to more people. While the MPO has not received any requests for oral language assistance at MPO-sponsored meetings in the past three years, this does not mean that there will not be a need in the future. To make sure that more people with LEP are aware of the MPO and services and programs it provides, staff will continue to improve its engagement with members of this population and community organizations that serve them. As new language data become available and approaches to assisting people with LEP change, this LAP will be revised.

1 Prior to 2016, French-based creole languages were coded as French Creole in the ACS. Because most of these speakers speak Haitian Creole, starting in 2016 Haitian Creole was recoded to Haitian, which includes Haitian Creole and all other mutually intelligible French-based creoles. This LAP uses this new terminology and definition, except when referring to Massachusetts Department of Education data, which uses the term Haitian Creole.

2 See: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/acs/tech-doc/user-notes/2016_Language_User_Note.pdf.

3 Where a PUMA includes towns on either side of the MPO boundary, a split factor was applied. This factor was estimated by first calculating the average Census-estimated population by town and PUMA for the years 2015–19. The factor is equal to the percentage of the PUMA total that falls within MPO municipalities.

4 This number of languages is significantly more than the 19 Safe Harbor languages reported in the 2017 LAP. This variance is likely due in part to the changes in how languages are coded, as described earlier in this document, and the difference in data sources (ACS summary tables versus PUMS data).

5 For spoken dialects, Chinese includes Mandarin and Cantonese. For written Chinese, the MPO translates documents into traditional and simplified Chinese. Prior to 2016, French-based creole languages were coded as French Creole in the ACS. Because most of these speakers speak Haitian Creole, starting in 2016 Haitian Creole was recoded to Haitian, which includes Haitian Creole and all other mutually intelligible French-based creoles. This LAP uses this new terminology and definition, except when referring to Massachusetts Department of Education data, which uses the term Haitian Creole.

6 For information about how to compare ACS language data before and after 2016, see https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/acs/tech-doc/user-notes/2016_Language_User_Note.pdf.

7 An ELL student is defined by the MDOE as “a student whose first language is a language other than English who is unable to perform ordinary classroom work in English.” http://profiles.doe.mass.edu/help/data.aspx?section=students#selectedpop.

8 A few public school districts include towns outside of the Boston region: King Phillips School District (which includes Plainville); Northboro-Southboro School District (which includes Northborough); Masconomet School District (which includes Boxborough); and the Nashoba School District (which includes Lancaster and Stow).

9 In the PUMS data, Somali is grouped with Amharic and other Afro-Asiatic languages, so the percentage that speak Somali is likely less than 1.1 percent.